As street protests in Turkey continue, and the government’s response has begun to harden, many are now talking about a coming ‘Turkish spring’. Burak Kadercan warns against such an analysis of these events, arguing that the protestors have no collective vision of change, and that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan remains a relatively popular leader. He writes that if the ruling AKP party is able to mobilise thousands of its supporters against the protestors we may well see the onset of full-blown authoritarianism and civil strife.

“What is happening in Turkey?” is a popular question these days, but it is the wrong one, for something has been happening in Turkey for quite some time. What the world has come to see lately is not the problem, but its symptoms. The symptoms are the country-wide protests and accompanying police brutality, which itself has come to be defined in terms of tear gas (or, simply “gas” in the Turkish lexicon). The problem is the increasing autocratic tendencies of Turkey’s ruling party of over 10 years (AKP), which are epitomized in the personal style of its Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

You may think that the protests in Turkey point towards the coming of a Turkish Spring. You would be wrong. Unless the government chooses wisely, however, we may be looking at the beginning of a long and harsh Turkish Winter. The protests unleashed an energy that cannot be undone but have yet to spread to the broader population. AKP has a long record of not backing down in the face of criticism. The demonstrators claim themselves to be an unstoppable force and the government, drawing upon its large support base (1 in every 2 votes according to 2011 elections), acts like an immovable object. These are not compatible philosophies and their clash may trigger a process that will then have dramatic consequences for Turkish democracy.

It All Started with a Tree

The chain of events started with a handful of peaceful protestors comprised largely of environmentalists and university students occupying Gezi Parkı, a relatively small park that is situated right by the Taksim Square, Istanbul’s cultural and financial center. Gezi Parkı was set to be demolished so that an Ottoman-era barracks that itself had been destroyed in 1940s in the same area could be reconstructed. The initial protestors were not criticizing the government per se, but a particular decision that they thought not only would destroy the only green space left in the center of the city, but also was forced on the city without proper dialogue and consultation with its inhabitants.

On May 28th, police forces responded with their signature method: gas. In an interesting twist — interesting for Turkish politics at least — the occupiers found extensive support from thousands, who responded not only to the destruction of Gezi Parkı, but also, and even more so, to the unprovoked police brutality that has become the norm and not the exception in the last couple of years. The increasing intensity of the “gas bombardment” triggered a chain reaction. Before anyone knew it, tens of thousands of citizens across the country, coordinating through Facebook and Twitter, took to the streets in order to show support for Taksim demonstrators. Faced with fierce resistance, the police retreated from Gezi Parkı and Taksim Square in the first days of June only to return on June 11, when they, citing the destabilizing effects of “marginal” and “terrorist” factions that infiltrated the ranks of the protestors, “cleared” the square, if not Gezi Parkı, by using overwhelming force (read “gas”). As this piece is being written, uncertainty is the only word that can define the situation.

Rage Against AKP: The Problem

If these are the symptoms, what is the problem? The problem reveals itself mostly in the identity of the protestors. They are not a homogenous group, bound neither by religious beliefs and ethnicity, nor by political affiliation. What unites them is their anger at AKP, but even more so, at Erdoğan. For them, the problem is obvious: Erdoğan’s AKP is slowly but surely becoming more intrusive and controlling over their lives. Erdoğan personally has taken the charge; he has authoritatively commented on various issues such as abortion and architecture, openly vilified atheists, categorized people who consumed alcohol on a “regular” basis – defined as drinking once a week – as alcoholics (but suggested that those who voted for AKP were not so), publicly disparaged journalists, prompted extensive educational reforms that introduced further religious elements to curricula despite mass protests, and so on.

In the eyes of his critics, Erdoğan’s position has come to be defined in terms of four interrelated components. First, Erdoğan’s discourses and policies about “change” tend to have references to religion in some shape or form, if never defined solely in religious terms. The more secular segments of the society find these references a little too discomforting. Second, Erdoğan’s discursive style has grown ever more disparaging, controlling, and devoid of any compassion for the very people who feel that their way of life is under attack. Third, Erdoğan’s charisma is built on an understanding that categorically rejects the practice of backing down under pressure, regardless of him being right or wrong. Fourth, Erdoğan does not take criticism lightly. This characteristic is increasingly scarier in a political environment where even journalists can no longer engage Erdoğan on critical terms without putting their careers at risk.

That Erdoğan’s all-powerful, all-knowing, and ever-present image is being projected into the lives of Turkish citizens make some segments of the society feel not only threatened by AKP’s incursions, but also increasingly voiceless. Under these circumstances, Gezi Parkı merely proved to be the last straw that broke camel’s back. But, make no mistake. Turkish politics will never be the same after Gezi Parkı protests. Until May 28th, AKP was convinced that it was an invincible force of nature in Turkish politics. After May 28th, AKP’s opponents will always think of similar protests if they feel their voices are being shut off by AKP. There is a new game in town now.

Given all these, are we looking at a “Turkish Spring?” Even the analogy itself is misleading for three reasons. First, Turkey’s democracy may have its flaws, but comparing Erdoğan’s Turkey circa June 2013 and Mubarak’s Egypt would be a mistake. Second, Erdoğan remains a popular leader. Even Erdoğan’s most ardent critic concedes that if there is an election tomorrow, AKP can still claim at least 45 per cent of the votes. Third, the protestors do not share or project a vision for revolution. While left-wing revolutionary factions have been active participants in the protests, their numbers and vision remain necessarily marginal. For most demonstrators, this is an exercise in letting the government know and understand that they are done with being told how to live, being called names and being reprimanded. There is a conscious attempt to brand all of the demonstrations as “resistance.” For most, this is all about pushing back against AKP’s incursions and telling AKP that they still have a voice.

AKP Pushes Back: Enter the Turkish Winter?

AKP’s response to the public outcry clearly demonstrates the depth and scope of the problem. Erdoğan immediately called protestors “looters.” Recently, AKP has differentiated between the “good” protestors and “bad” ones, suggesting that the latter are hijacking the demonstrations to provoke chaos and instability in Turkey. Such criminalization, undoubtedly, is meant to legitimize the relevant police brutality in the eyes of some of the spectators.

Most alarmingly, Erdoğan announced that AKP was “barely restraining” the so-called “fifty per cent” (which stands for AKP voters per 2011 elections), suggesting that if the opposition brings “one hundred thousand” demonstrators to the streets, he can easily summon “one million” to counter them. AKP is now gearing up for “solidarity meetings” to be held among AKP sympathizers in Ankara and Istanbul on the 14th and 15th of June. For Erdoğan, they are meant to be displays of his power, which itself is built on the so-called fifty percent. The messages behind this move are hard to miss. First, the protestors are not “the people,” only “some” people. Second, there is a silent crowd that supports AKP and opposes the protestors. Third, if conditions change, the fifty per cent can confront the demonstrators in the streets. These are the kinds of messages that one can interpret to be the harbinger of a Turkish Winter.

What is the rationale behind such pessimism? While it is true that Gezi Parkı has unleashed a kinetic energy in the political arena, this energy has so far failed to spread across the broader population. We are not looking at a case of “people versus Erdoğan” yet. However, this energy will also be difficult, if not impossible, for AKP to contain. If its past record tells us anything, AKP will try to do exactly that: containing the spread of the symptoms as opposed to solving the problem. This time, it seems very likely that AKP will openly invoke the support of its “silent” fifty percent in order to do that.

In this context, three possibilities await Turkey’s political future. First, if AKP, with or without Erdoğan, chooses to reconcile with the demonstrators and come to terms with what has made the party (and Erdoğan) a magnet of anger and fear among some segments of the society, Turkish democracy will survive this episode and emerge stronger than ever. If Erdoğan’s AKP refuses to come to terms with itself, it is very likely that we will soon be talking about the Turkish Winter, marked by either full-blown authoritarianism or civil strife (or both).

What I refer to as political winter involves two scenarios. In the first scenario, AKP tightens its grip on the lives of its opponents in order to contain the demonstrations and prevent further ones. The streets may witness further protests from angrier and more radicalized protestors, which will then trigger further and harsher reactions from the government, fueling a spiral at the end of which AKP can no longer sustain its rule short of initiating explicitly authoritarian measures. AKP has so far refrained from such measures, but if the situation deteriorates, its hand may be forced.

An even worse scenario is one where neither the demonstrators nor AKP can control the popular energies. If this scenario materializes, all bets are off. The second half of 1970s is a cold reminder of how bloody things can get in Turkey once the society is polarized over “where Turkey should go.” Back then, it was left-wing versus right-wing clashes that pushed the entire country into the arms of a low-intensity civil war. If such polarization rears its ugly head again, it will include religion as an important component of the clash, and the image of a rising Turkey will be replaced by something considerably darker for the foreseeable future.

The ball is now in Erdoğan’s court. With the right move, Turkish democracy will shed yet another one of its old habits — in this case, the tendency of powerful political parties to drift into populism-fuelled authoritarianism. With the wrong move, the hazy days of May and June may pave the way for a long and harsh Turkish Winter. Erdoğan may choose to step on the brakes, which will require him to revise his discourse and policies but will also allow him to keep the image of a rising and democratic Turkey alive and kicking. The real challenge for him is to resist the temptation of playing down and repressing the symptoms that are now revealing themselves all over Turkey through the same mindset that has caused the problem in the first place.

A version of this article originally appeared at http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2013/06/13/turkish-winter/#Author

About the author

Burak Kadercan – University of Reading

Burak Kadercan is a Lecturer in International Relations, in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Reading. He specializes in the intersection of international relations theory, international security, military-diplomatic history, and political geography.

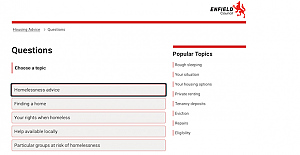

Enfield Labour welcomes new court order to stop antisocial behaviour in Edmonton Green

Enfield Labour welcomes new court order to stop antisocial behaviour in Edmonton Green David Lammy arrives in Downing Street after becoming deputy prime minister

David Lammy arrives in Downing Street after becoming deputy prime minister CTCA UK Condemns the Political Forcing Out of Afzal Khan MP for Engaging with Turkish Cypriots

CTCA UK Condemns the Political Forcing Out of Afzal Khan MP for Engaging with Turkish Cypriots Tatar: “Reaction to MP’s TRNC visit is yet another stark example of the Greek Cypriot leadership’s primitive and domineering mentality”

Tatar: “Reaction to MP’s TRNC visit is yet another stark example of the Greek Cypriot leadership’s primitive and domineering mentality” 102nd Anniversary Celebration Ball of the Republic of Türkiye in London

102nd Anniversary Celebration Ball of the Republic of Türkiye in London Latest! Israeli navy intercepts Global Sumud Flotilla as it approaches Gaza to break siege

Latest! Israeli navy intercepts Global Sumud Flotilla as it approaches Gaza to break siege Enfield Labour Calls for Public Feedback on Crime and Safety Concerns

Enfield Labour Calls for Public Feedback on Crime and Safety Concerns Important Travel Updates: London Underground and DLR Strike Action

Important Travel Updates: London Underground and DLR Strike Action Champions League, Liverpool lose at Galatasaray

Champions League, Liverpool lose at Galatasaray Liverpool flew out for their Champions League match against Galatasaray

Liverpool flew out for their Champions League match against Galatasaray Enfield Council has approved plans for Surf London

Enfield Council has approved plans for Surf London Zlatan Ibrahimović receives UEFA President’s Award

Zlatan Ibrahimović receives UEFA President’s Award Maritime Finance and Sustainability Take Centre Stage at LISW25 Gala Dinner

Maritime Finance and Sustainability Take Centre Stage at LISW25 Gala Dinner London welcomes traders back to the reopened Seven Sisters Market

London welcomes traders back to the reopened Seven Sisters Market Enfield’s Crews Hill and Chase Park shortlisted for potential New Town

Enfield’s Crews Hill and Chase Park shortlisted for potential New Town Important milestone achieved with no hotel placements for temporary accommodation

Important milestone achieved with no hotel placements for temporary accommodation