n a historic sitting of the House of Commons on Saturday, British lawmakers will consider a newly reached Brexit deal some three-and-a-half years after a referendum that set the U.K. on a course to divorce the European Union.

But real progress in leaving the controversial Brexit issue behind seems unlikely, as the parliamentary math spells a herculean task for the prime minister to wrangle the necessary votes.

Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party has the largest number of seats in parliament’s lower house, but lacks a majority, so he still needs the backing of Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), his de facto governance partners.

Arlene Foster, the DUP leader, has already said they would not support Johnson’s deal as it stands, playing the same tune as all the opposition parties and putting before the prime minister a high mountain to climb in Westminster.

If Johnson’s calls to all MPs to get behind his deal fall on deaf ears – currently a very likely prospect – the deal will be voted down.

What steps the opposition can introduce to further force Johnson to request an extension to the Oct. 31 deadline will be shaped by amendments during the historic and rare Saturday sitting.

Johnson has been adamant that he would not seek an extension – saying he would rather be “dead in a ditch” than ask for one – but he is also obliged to follow the law of land and request an extension as mandated by the Benn act.

He has said it is either this new deal or "no deal," arguing that the EU would not grant another extension beyond Oct. 31.

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, however, left the door open for a further extension, telling journalists that he would take the message to member countries and get their views if such a request arises.

DUP objection

Lending 10 MPs in a “confidence and supply” deal, the DUP has acted like a partner in governance since the Conservatives lost their majority in the House in the 2017 snap elections.

From the start, Northern Ireland’s unionist party has categorically objected to the idea of any deal that would introduce a customs border between the U.K. region and the rest of the kingdom.

The new deal, however, does exactly that, and so is unacceptable for the DUP as a party that prioritizes the union with the U.K. as its raison d'etre.

The kingdom’s future

As the 1998 Belfast Agreement – also known as the Good Friday Agreement – stipulates that voters in Northern Ireland can have a referendum to unite with the Republic of Ireland, many nationalists think the iron might be hot for such a vote.

Northern Ireland voted in 1973 to remain in the EU and the new deal, if ratified by Westminster, will keep them in the EU to some certain degree, adding to the worries of unionists in the region. Under the deal, the border would remain as is, with the local assembly having the right to review to leave EU regulations every four years.

Many commentators think this could be the start of the unification of two Irish states.

Calls for a second independence referendum in Scotland have been made since the 2016 EU referendum, but now they are growing louder and clearer.

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said such a referendum would be held next year, barring Scotland from being "dragged out of the EU with the rest of the U.K.”

In the 2016 referendum, Scots were squarely on the Remain side, with 62% of them voting to stay in the EU, and the majority would still like to remain a member of the bloc.

They now think their case is even stronger with the British concession on Northern Ireland in exchange for the new Brexit deal.

A second referendum might well end the Kingdom of Great Britain, which has existed for over 300 years, since the Acts of Union in 1707.

So Brexit, one of the most divisive factors in British society and the kingdom, could actually bring down the curtain on the once-mighty United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, downsizing it within a few years to the Kingdom of England and Wales.

Enfield Labour welcomes new court order to stop antisocial behaviour in Edmonton Green

Enfield Labour welcomes new court order to stop antisocial behaviour in Edmonton Green David Lammy arrives in Downing Street after becoming deputy prime minister

David Lammy arrives in Downing Street after becoming deputy prime minister CTCA UK Condemns the Political Forcing Out of Afzal Khan MP for Engaging with Turkish Cypriots

CTCA UK Condemns the Political Forcing Out of Afzal Khan MP for Engaging with Turkish Cypriots Tatar: “Reaction to MP’s TRNC visit is yet another stark example of the Greek Cypriot leadership’s primitive and domineering mentality”

Tatar: “Reaction to MP’s TRNC visit is yet another stark example of the Greek Cypriot leadership’s primitive and domineering mentality” 102nd Anniversary Celebration Ball of the Republic of Türkiye in London

102nd Anniversary Celebration Ball of the Republic of Türkiye in London Latest! Israeli navy intercepts Global Sumud Flotilla as it approaches Gaza to break siege

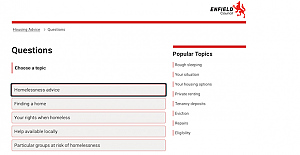

Latest! Israeli navy intercepts Global Sumud Flotilla as it approaches Gaza to break siege Enfield Labour Calls for Public Feedback on Crime and Safety Concerns

Enfield Labour Calls for Public Feedback on Crime and Safety Concerns Important Travel Updates: London Underground and DLR Strike Action

Important Travel Updates: London Underground and DLR Strike Action Champions League, Liverpool lose at Galatasaray

Champions League, Liverpool lose at Galatasaray Liverpool flew out for their Champions League match against Galatasaray

Liverpool flew out for their Champions League match against Galatasaray Enfield Council has approved plans for Surf London

Enfield Council has approved plans for Surf London Zlatan Ibrahimović receives UEFA President’s Award

Zlatan Ibrahimović receives UEFA President’s Award Maritime Finance and Sustainability Take Centre Stage at LISW25 Gala Dinner

Maritime Finance and Sustainability Take Centre Stage at LISW25 Gala Dinner London welcomes traders back to the reopened Seven Sisters Market

London welcomes traders back to the reopened Seven Sisters Market Enfield’s Crews Hill and Chase Park shortlisted for potential New Town

Enfield’s Crews Hill and Chase Park shortlisted for potential New Town Important milestone achieved with no hotel placements for temporary accommodation

Important milestone achieved with no hotel placements for temporary accommodation